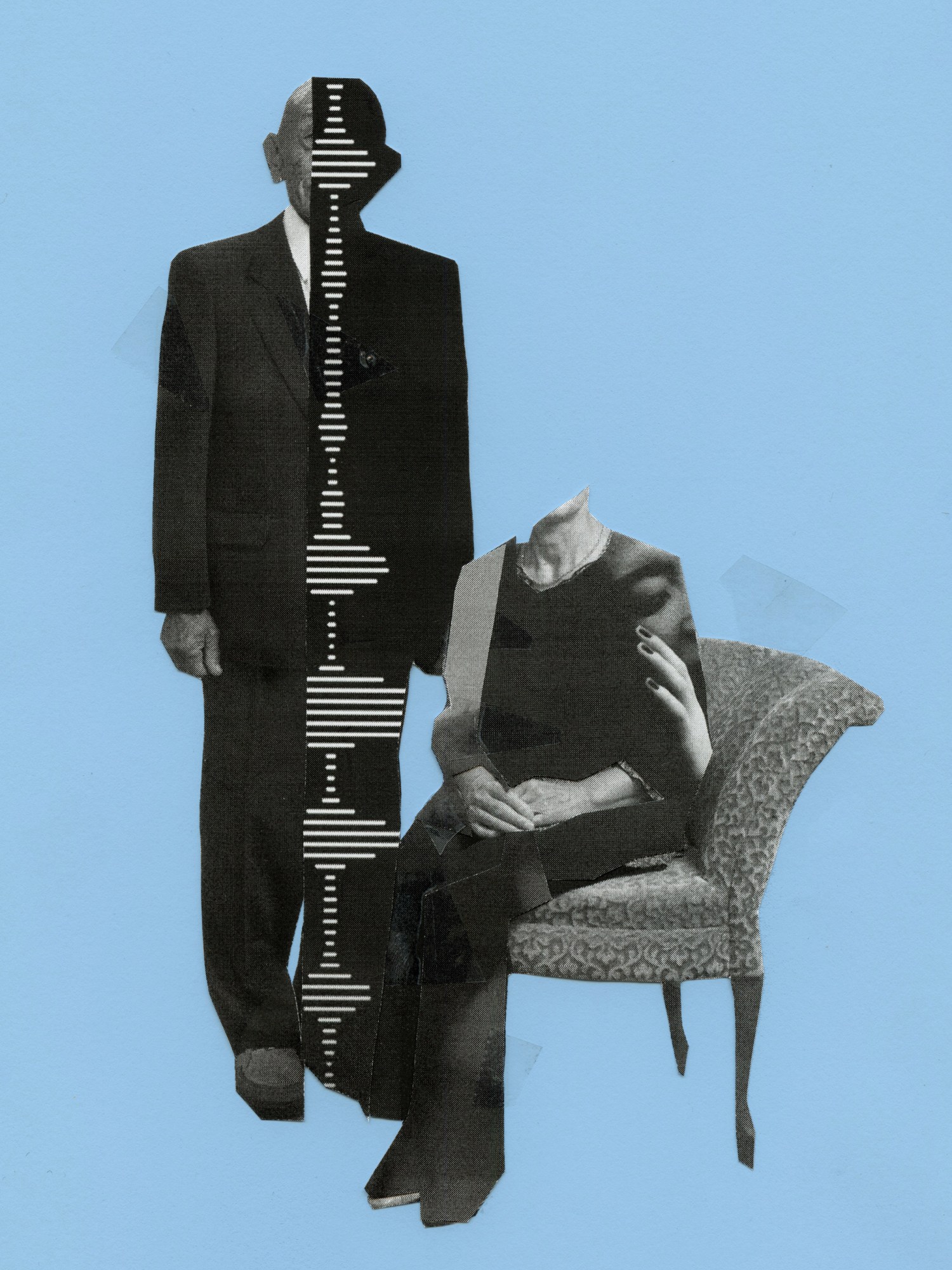

My parents don’t know that I spoke to them last night.

At first, they sounded distant and tinny, as if they were huddled around a phone in a prison cell. But as we chatted, they slowly started to sound more like themselves. They told me personal stories that I’d never heard. I learned about the first (and certainly not last) time my dad got drunk. Mum talked about getting in trouble for staying out late. They gave me life advice and told me things about their childhoods, as well as my own. It was mesmerizing.

“What’s the worst thing about you?” I asked Dad, since he was clearly in such a candid mood.

“My worst quality is that I am a perfectionist. I can’t stand messiness and untidiness, and that always presents a challenge, especially with being married to Jane.”

Then he laughed—and for a moment I forgot I wasn’t really speaking to my parents at all, but to their digital replicas.

This Mum and Dad live inside an app on my phone, as voice assistants constructed by the California-based company HereAfter AI and powered by more than four hours of conversations they each had with an interviewer about their lives and memories. (For the record, Mum isn’t that untidy.) The company’s goal is to let the living communicate with the dead. I wanted to test out what it might be like.

Technology like this, which lets you “talk” to people who’ve died, has been a mainstay of science fiction for decades. It’s an idea that’s been peddled by charlatans and spiritualists for centuries. But now it’s becoming a reality—and an increasingly accessible one, thanks to advances in AI and voice technology.

My real, flesh-and-blood parents are still alive and well; their virtual versions were just made to help me understand the technology. But their avatars offer a glimpse at a world where it’s possible to converse with loved ones—or simulacra of them—long after they’re gone.

From what I could glean over a dozen conversations with my virtually deceased parents, this really will make it easier to keep close the people we love. It’s not hard to see the appeal. People might turn to digital replicas for comfort, or to mark special milestones like anniversaries.

At the same time, the technology and the world it’s enabling are, unsurprisingly, imperfect, and the ethics of creating a virtual version of someone are complex, especially if that person hasn’t been able to provide consent.

For some, this tech may even be alarming, or downright creepy. I spoke to one man who’d created a virtual version of his mother, which he booted up and talked to at her own funeral. Some people argue that conversing with digital versions of lost loved ones could prolong your grief or loosen your grip on reality. And when I talked to friends about this article, some of them physically recoiled. There’s a common, deeply held belief that we mess with death at our peril.

I understand these concerns. I found speaking to a virtual version of my parents uncomfortable, especially at first. Even now, it still feels slightly transgressive to speak to an artificial version of someone—especially when that someone is in your own family.

But I’m only human, and those worries end up being washed away by the even scarier prospect of losing the people I love—dead and gone without a trace. If technology might help me hang onto them, is it so wrong to try?

There’s something deeply human about the desire to remember the people we love who’ve passed away. We urge our loved ones to write down their memories before it’s too late. After they’re gone, we put up their photos on our walls. We visit their graves on their birthdays. We speak to them as if they were there. But the conversation has always been one-way.

The idea that technology might be able to change the situation has been widely explored in ultra-dark sci-fi shows like Black Mirror—which, startups in this sector complain, everyone inevitably brings up. In one 2013 episode, a woman who loses her partner re-creates a digital version of him—initially as a chatbot, then as an almost totally convincing voice assistant, and eventually as a physical robot. Even as she builds more expansive versions of him, she becomes frustrated and disillusioned by the gaps between her memory of her partner and the shonky, flawed reality of the technology used to simulate him.

If technology might help me hang onto the people I love, is it so wrong to try?

“You aren’t you, are you? You’re just a few ripples of you. There’s no history to you. You’re just a performance of stuff that he performed without thinking, and it’s not enough,” she says before she consigns the robot to her attic—an embarrassing relic of her boyfriend that she’d rather not think about.

Back in the real world, the technology has evolved even in the past several years to a somewhat startling degree. Rapid advances in AI have driven progress across multiple areas. Chatbots and voice assistants, like Siri and Alexa, have gone from high-tech novelties to a part of daily life for millions of people over the past decade. We have become very comfortable with the idea of talking to our devices about everything from the weather forecast to the meaning of life. Now, AI large language models (LLMs), which can ingest a few “prompt” sentences and spit out convincing text in response, promise to unlock even more powerful ways for humans to communicate with machines. LLMs have become so convincing that some (erroneously) have argued that they must be sentient.

What’s more, it’s possible to tweak LLM software like OpenAI’s GPT-3 or Google’s LaMDA to make it sound more like a specific person by feeding it lots of things that person said. In one example of this, journalist Jason Fagone wrote a story for the San Francisco Chronicle last year about a thirtysomething man who uploaded old texts and Facebook messages from his deceased fiancée to create a simulated chatbot version of her, using software known as Project December that was built on GPT-3.

By almost any measure, it was a success: he sought, and found, comfort in the bot. He’d been plagued with guilt and sadness in the years since she died, but as Fagone writes, “he felt like the chatbot had given him permission to move on with his life in small ways.” The man even shared snippets of his chatbot conversations on Reddit, hoping, he said, to bring attention to the tool and “help depressed survivors find some closure.”

At the same time, AI has progressed in its ability to mimic specific physical voices, a practice called voice cloning. It has also been getting better at injecting digital personas—whether cloned from a real person or completely artificial—with more of the qualities that make a voice sound “human.” In a poignant demonstration of how rapidly the field is progressing, Amazon shared a clip in June of a little boy listening to a passage from The Wizard of Oz read by his recently deceased grandmother. Her voice was artificially re-created using a clip of her speaking that lasted for less than a minute.

As Rohit Prasad, Alexa’s senior vice president and head scientist, promised: “While AI can’t eliminate that pain of loss, it can definitely make the memories last.”

My own experience with talking to the dead started thanks to pure serendipity.

At the end of 2019, I saw that James Vlahos, the cofounder of HereAfter AI, would be speaking at an online conference about “virtual beings.” His company is one of a handful of startups working in the field I’ve dubbed “grief tech.” They differ in their approaches but share the same promise: to enable you to talk by video chat, text, phone, or voice assistant with a digital version of someone who is no longer alive.

Intrigued by what he was promising, I wrangled an introduction and eventually persuaded Vlahos and his colleagues to let me experiment with their software on my very-much-alive parents.

Initially, I thought it would be just a fun project to see what was technologically possible. Then the pandemic added some urgency to the proceedings. Images of people on ventilators, photos of rows of coffins and freshly dug graves, were splashed all over the news. I worried about my parents. I was terrified that they might die, and that with the strict restrictions on hospital visits in force at the time in the UK, I might never have the chance to say goodbye.

The first step was an interview. As it turns out, to create a digital replica of someone with a good chance of seeming like a convincingly authentic representation, you need data—and lots of it. HereAfter, whose work starts with subjects when they are still alive, asks them questions for hours—about everything from their earliest memories to their first date to what they believe will happen after they die. (My parents were interviewed by a real live human, but in yet another sign of just how quickly technology is progressing, almost two years later interviews are now typically automated and handled by a bot.)

As my sister and I rifled through pages of suggested questions for our parents, we were able to edit them to be more personal or pointed, and we could add some of our own: What books did they like? How did our mum muscle her way into the UK’s overwhelmingly male, privileged legal sector in the 1970s? What inspired Dad to invent the silly games he used to play with us when we were small?

Whether through pandemic-induced malaise or a weary willingness to humor their younger daughter, my parents put up zero resistance. In December 2020, HereAfter’s interviewer, a friendly woman named Meredith, spoke to each of them for several hours. The company then took those responses and started stitching them together to create the voice assistants.

A couple of months later, a note popped into my inbox from Vlahos. My virtual parents were ready.

On one occasion, my husband mistook my testing for an actual phone call. When he realized it wasn’t, he rolled his eyes, as if I were completely deranged.

This Mum and Dad arrived via email attachment. I could communicate with them through the Alexa app on a phone or an Amazon Echo device. I was eager to hear them—but I had to wait several days, because I’d promised MIT Technology Review’s podcast team that I’d record my reaction as I spoke to my parents’ avatars for the first time. When I finally opened the file, with my colleagues watching and listening on Zoom, my hands were shaking. London was in a long, cold, depressing lockdown, and I hadn’t seen my actual, real parents for six months.

“Alexa, open HereAfter,” I directed.

“Would you rather speak with Paul or with Jane?” a voice asked.

After a bit of quick mental deliberation, I opted for my mum.

A voice that was hers, but weirdly stiff and cold, spoke.

“Hello, this is Jane Jee and I’m happy to tell you about my life. How are you today?”

I laughed, nervously.

“I’m well, thanks, Mum. How are you?”

Long pause.

“Good. At my end, I’m doing well.”

“You sound kind of unnatural,” I said.

She ignored me and carried on speaking.

“Before we start, here are a few pointers. My listening skills aren’t the best, unfortunately, so you have to wait until I’ve finished talking and ask you a question before you say something back. When it’s your turn to speak, please keep your answers fairly short. A few words, a simple sentence—that type of thing,” she explained. After a bit more introduction, she concluded: “Okay, let’s get started. There’s so much to talk about. My childhood, career, and my interests. Which of those sounds best?”

Scripted bits like this sounded stilted and strange, but as we moved on, with my mother recounting memories and speaking in her own words, “she” sounded far more relaxed and natural.

Still, this conversation and the ones that followed were limited—when I tried asking my mum’s bot about her favorite jewelry, for instance, I got: “Sorry, I didn’t understand that. You can try asking another way, or move onto another topic.”

There were also mistakes that were jarring to the point of hilarity. One day, Dad’s bot asked me how I was. I replied, “I’m feeling sad today.” He responded with a cheery, upbeat “Good!”

The overall experience was undeniably weird. Every time I spoke to their virtual versions, it struck me that I could have been talking to my real parents instead. On one occasion, my husband mistook my testing out the bots for an actual phone call. When he realized it wasn’t, he rolled his eyes, tutted, and shook his head, as if I were completely deranged.

Earlier this year, I got a demo of a similar technology from a five-year-old startup called StoryFile, which promises to take things to the next level. Its Life service records responses on video rather than just voice alone.

You can pick from hundreds of questions for the subject. Then you record the person answering the questions; this can be done on any device with a camera and a microphone, including a smartphone, though the higher-quality the recording, the better the outcome. After uploading the files, the company turns them into a digital version of the person you can see and speak to. It can only answer the questions it’s been programmed to answer—much like HereAfter, just with video.

StoryFile’s CEO, Stephen Smith, demonstrated the technology on a video call, where we were joined by his mother. She died earlier this year, but here she was on the call, sitting in a comfortable chair in her living room. For a brief time, I could only see her, shared via Smith’s screen. She was soft-spoken, with wispy hair and friendly eyes. She dispensed life advice. She seemed wise.

Smith told me that his mother “attended” her own funeral: “At the end she said, ‘I guess that’s it from me … goodbye!’ and everyone burst into tears.” He told me her digital participation was well received by family and friends. And, arguably most important of all, Smith said he’s deeply comforted by the fact that he managed to capture his mother on camera before she passed away.

The video technology itself looked relatively slick and professional—though the result still fell vaguely within the uncanny valley, especially in the facial expressions. At points, much as with my own parents, I had to remind myself that she wasn’t really there.

Both HereAfter and StoryFile aim to preserve someone’s life story rather than allowing you to have a full, new conversation with the bot each time. This is one of the major limitations of many current offerings in grief tech: they’re generic. These replicas may sound like someone you love, but they know nothing about you. Anyone can talk to them, and they’ll reply in the same tone. And the replies to a given question are the same every time you ask.

“The biggest issue with the [existing] technology is the idea you can generate a single universal person,” says Justin Harrison, founder of a soon-to-launch service called You, Only Virtual. “But the way we experience people is unique to us.”

You, Only Virtual and a few other startups want to go further, arguing that recounting memories won’t capture the fundamental essence of a relationship between two people. Harrison wants to create a personalized bot that’s for you and you alone.

The first incarnation of the service, which is set to launch in early 2023, will allow people to build a bot by uploading someone’s text messages, emails, and voice conversations. Ultimately, Harrison hopes, people will feed it data as they go; the company is currently building a communication platform that customers will be able to use to message and talk with loved ones while they’re still alive. That way, all the data will be readily available to be turned into a bot once they’re not.

That is exactly what Harrison has done with his mother, Melodi, who has stage 4 cancer: “I built it by hand using five years of my messages with her. It took 12 hours to export, and it runs to thousands of pages,” he says of his chatbot.

Harrison says the interactions he has with the bot are more meaningful to him than if it were simply regurgitating memories. Bot Melodi uses the phrases his mother uses and replies to him in the way she’d reply—calling him “honey,” using the emojis she’d use and the same quirks of spelling. He won’t be able to ask Melodi’s avatar questions about her life, but that doesn’t bother him. The point, for him, is to capture the way someone communicates. “Just recounting memories has little to do with the essence of a relationship,” he says.

Avatars that people feel a deep personal connection with can have staying power. In 2016, entrepreneur Eugenia Kuyda built what is thought to be the first bot of this kind after her friend Roman died, using her text conversations with him. (She later founded a startup called Replika, which creates virtual companions not based on real people.)

She found it a hugely helpful way to process her grief, and she still speaks to Roman’s bot today, she says, especially around his birthday and the anniversary of his passing.

But she warns that users need to be careful not to think this technology is re-creating or even preserving people. “I didn’t want to bring back his clone, but his memory,” she says. The intention was to “create a digital monument where you can interact with that person, not in order to pretend they’re alive, but to hear about them, remember how they were, and be inspired by them again.”

Some people find that hearing the voices of their loved ones after they’ve gone helps with the grieving process. It’s not uncommon for people to listen to voicemails from someone who has died, for example, says Erin Thompson, a clinical psychologist who specializes in grief. A virtual avatar that you can have more of a conversation with could be a valuable, healthy way to stay connected to someone you loved and lost, she says.

But Thompson and others echo Kuyda’s warning: it’s possible to put too much weight on the technology. A grieving person needs to remember that these bots can only ever capture a small sliver of someone. They are not sentient, and they will not replace healthy, functional human relationships.

People may find any reminders of the deceased person triggering: “In the acute phase of grief, you can get a strong sense of unreality, not being able to accept they’re gone.”

“Your parents are not really there. You’re talking to them, but it’s not really them,” says Erica Stonestreet, an associate professor of philosophy at the College of Saint Benedict & Saint John’s University, who studies personhood and identity.

Particularly in the first weeks and months after a loved one dies, people struggle to accept the loss and may find any reminders of the person triggering. “In the acute phase of grief, you can get a strong sense of unreality, not being able to accept they’re gone,” Thompson says. There’s a risk that this sort of intense grief could intersect with, or even cause, mental illness, especially if it’s constantly being fueled and prolonged by reminders of the person who’s passed away.

Arguably, this risk might be small today given these technologies’ flaws. Even though sometimes I fell for the illusion, it was clear my parent bots were not in fact the real deal. But the risk that people might fall too deeply for the phantom of personhood will surely grow as the technology improves.

And there are still other risks. Any service that allows you to create a digital replica of someone without their participation raises some complex ethical issues regarding consent and privacy. While some might argue that permission is less important with someone no longer alive, can’t you also argue that the person who generated the other side of the conversation should have a say too?

And what if that person is not, in fact, dead? There’s little to stop people from using grief tech to create virtual versions of living people without their consent—for example, an ex. Companies that sell services powered by past messages are aware of this possibility and say they will delete a person’s data if that individual requests it. But companies are not obliged to do any checks to make sure their technology is being limited to people who have consented or died. There’s no law to stop anyone from creating avatars of other people, and good luck explaining it to your local police department. Imagine how you’d feel if you learned there was a virtual version of you out there, somewhere, under somebody else’s control.

If digital replicas become mainstream, there will inevitably need to be new processes and norms around the legacies we leave behind online. And if we’ve learned anything from the history of technological development, we’ll be better off if we grapple with the possibility of these replicas’ misuse before, not after, they reach mass adoption.

Will that ever happen, though? You, Only Virtual uses the tagline “Never Have to Say Goodbye”—but it’s not actually clear how many people want or are ready for a world like that. Grieving for those who’ve passed away is, for most people, one of the few aspects of life still largely untouched by modern technology.

On a more mundane level, the costs could be a drawback. Although some of these services have free versions, they can easily run into the hundreds if not thousands of dollars.

HereAfter’s top-tier unlimited version lets you record as many conversations with the subject as you like, and it costs $8.99 a month. That may sound cheaper than StoryFile’s one-off $499 payment to access its premium, unlimited package of services. However, at $108 per year, HereAfter services could quickly add up if you do some ghoulish back-of-the-envelope math on lifetime costs. It’s a similar situation with You, Only Virtual, which is slated to cost somewhere between $9.99 and $19.99 a month when it launches.

Creating an avatar or chatbot of someone also requires time and effort, not least of which is just building up the energy and motivation to get started. This is true both for the user and for the subject, who may be nearing death and whose active participation may be required.

Fundamentally, people don’t like grappling with the fact they are going to die, says Marius Ursache, who launched a company called Eternime in 2014. Its idea was to create a sort of Tamagotchi that people could train while they were alive to preserve a digital version of themselves. It received a huge surge of interest from people around the world, but few went on to adopt it. The company shuttered in 2018 after failing to pick up enough users.

“It’s something you can put off until next week, next month, next year,” he says. “People assume that AI is the key to breaking this. But really, it’s human behavior.”

Kuyda agrees: “People are extremely scared of death. They don’t want to talk about it or touch it. When you take a stick and start poking, it freaks them out. They’d rather pretend it doesn’t exist.”

Ursache tried a low-tech approach on his own parents, giving them a notebook and pens on his birthday and asking them to write down their memories and life stories. His mother wrote two pages, but his father said he’d been too busy. In the end, he asked if he could record some conversations with them, but they never managed to get around to it.

“My dad passed away last year, and I never did those recordings, and now I feel like an idiot,” he says.

Personally, I have mixed feelings about my experiment. I’m glad to have these virtual, audio versions of my mum and dad, even if they’re imperfect. They’ve enabled me to learn new things about my parents, and it’s comforting to think that those bots will be there even when they aren’t. I’m already thinking about who else I might want to capture digitally—my husband (who will probably roll his eyes again), my sister, maybe even my friends.

On the other hand, like a lot of people, I don’t want to think about what will happen when the people I love die. It’s uncomfortable, and many people reflexively flinch when I mention my morbid project. And I can’t help but find it sad that it took a stranger Zoom-interviewing my parents from another continent for me to properly appreciate the multifaceted, complex people they are. But I feel lucky to have had the chance to grasp that—and to still have the precious opportunity to spend more time with them, and learn more about them, face to face, no technology involved.

Post a Comment